Understanding and engaging with legislation, policies and standards

Higher Education (HE) works under various pieces of educational legislation as well as local and institutional policies. Professional and vocational programmes will also have to consider the requirements of registration bodies such as the Ministry of Justice which oversees the Professional Qualification in Probation.

Recognised bodies are HE institutions that can award a degree, therefore DMU acts as an awarding body for many of our partner institutions. In the DLAT team, part of my responsibilities is to support our partner institutions. Therefore, I need to be aware of current legislation and guidance that effects both the university and our partner institution.

Being part of a wider network keeps me informed of changes to legislation and guidelines. Therefore, I am a member of AdvanceHE and ALT mailing lists.

a) Understanding and engaging with legislation

Equality is an important consideration in Higher Education (HE) and includes accessibility. I am aware of how special educational needs can affect a student in a personal as well as a professional capacity. I have a son who is profoundly deaf and therefore throughout his education I have seen how important ensuring his communication needs are acknowledged and accommodated can be. Too often in school he was sat in front of a video with no subtitles and no transcript and people were then surprised if he misbehaved or did not understand the lesson, despite him being a very bright and able pupil.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) is responsible for enforcing the Public Sector Bodies (Websites and Mobile Applications) (No. 2) Accessibility Regulations 2018 (the ‘accessibility regulations’). As part of the DLAT team’s effort to ensure our websites meet these regulations I reviewed webpages on our DLAT Hub to ensure they met the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 standard.

Higher Education must also adhere to The Equality Act 2010, the UK legislation that provides protection to individuals with protected characteristics and prevents discrimination.

I create pedagogic and technology guidance available online via the DLAT Hub to support staff who are new to online working and teaching. These included accessible online resources for staff from a range of disciplines. I always ensure service provision is accessible and is aligned with good practice and professional guidelines, by ensuring all guidance I create fulfils the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). For example, all guidance videos I produce have subtitles for the hard of hearing and transcripts are added if possible. When producing learning resources, I also always ensure that they are accessible and comply with WCAG standards, if appropriate. I make use of MS Office Accessibility Checkers when creating Word, Excel or PowerPoint documents.

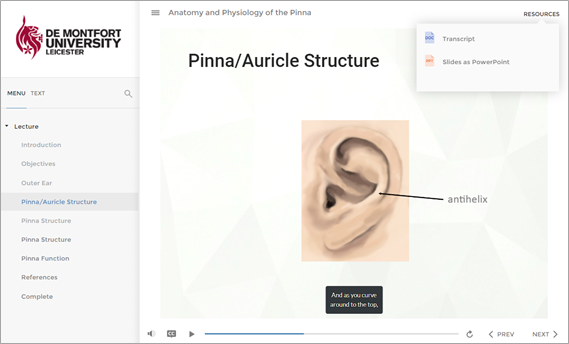

I reviewed the accessibility of Articulate Storyline and Articulate Rise and was responsible for creating the university’s original accessibility guidance for implementing these applications in June 2021. Providing guidance was important because Rise, in particular, did not initially conform to WCAG standards and authors needed to be made aware of what tools fell outside of the regulations.

De Montfort University has adhered to the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) model since October 2015. Making academic staff aware of the UDL principles of student engagement, representation of content and action and expression, in relation to digital and online learning has been part of the DLAT team’s responsibilities. Thus, part of my role has included demonstrating to academic staff how they can most effectively provide accessible resources for their students within the UDL model at DMU.

One important thing I have learnt from working with UDL is that providing accessible documents improves the learning experience for all students. A further important realization has been recognising how easy it can be for colleagues and oneself to discriminate without realising it, when we fail to consider the wide diversity of our students and their individual learning environments.

As I have always considered accessibility when developing learning resources or guidance, I have not normally needed to amend resources due to changes in legislation. However, I feel I could improve my audio descriptions and this is an aspect of my practice that I will focus on in future.

However, I’m also aware that I can occasionally focus on accessibility to the detriment of other areas of discrimination when creating resources. Therefore, I do try to be more conscious of my unconscious biases when creating learning resources. Working with the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) team and also our TNE partner institutions has been helpful in this regard.

I have been delighted to discover that all students benefit when resources are made fully accessible and anyone can experience problems trying to access resources. For example, trying to listen to a lecture on a noisy train journey is less frustrating for all users when subtitles or a transcript is made available.

b) Second legislative area, or understanding and engaging with policies and standards

At DMU, when a programme goes to validation or re-validation it needs to include a signed off copy of the ELT checklist contained in the ‘Programme Development Tool: Enhancing Learning through Technology [ELT] Strategy’. Requiring programme teams to complete this checklist ensures the team has carefully considered the use of technologies in their curriculum. I have responsibility for reviewing the ELT Checklist documents submitted for validation of programmes delivered by our Transnational Education (TNE) Partners. During ELT checklist review I add comments and provide further guidance where appropriate as to how teaching teams can use ELT to support their students and adhere to DMU policies. For example, the ELT checklist enables programme teams to demonstrate how they meet the DMU threshold for the use of technologies in the curriculum. When completing the ELT checklist, TNE programme teams are advised to contact myself as their DLAT consultant for guidance. This is where I can make suggestions as to how they can meet this threshold, for example, by explaining accessibility requirements so they can meet the first threshold. I can also direct academic colleagues to relevant guidance and policies, such as the QAA UK Quality Code for HE, the JISC Legal Guidelines for the use of Web 2.0 tools and any relevant DMU DLAT curriculum support materials.

The email below (figure11) shows the positive response from one of our TNE partner institutions after a review of their ELT checklist.

On reflection, I realise that by reviewing ELT Checklists as part of the programme validation process for TNEs, I am able to acquire a much clearer idea of what our TNE partners expect from the online technologies that DMU provides. Partner institutions can have quite a different perspective from our UK colleagues and may also be less aware of the policies they need to work under at DMU, such as the DMU Replay policy. Moreover, such TNE partners will also have their own additional national or institutional policies and governance to consider.

Too often in the past, I have found that the programme team does not contact me early enough on in the validation process, and that they complete their ELT Checklist without requesting my advice beforehand. My contribution is then restricted to responding to comments they provide in their completed ELT Checklist document, when I remind them that the DLAT team is always available for ELT support. Often, programme teams fail to fully consider how they might effectively use the more interactive elements of online technologies in their curriculum, which can lead to missed opportunities for their students’ online experience. I find this frustrating, as I would like to be able to provide advice earlier on in the process. Consequently, I am now trying to be more visible to my International Partnership colleagues so they can recommend that programme teams contact me, or my DLAT team colleagues, earlier on in the process of validations and tenders.

On a positive note, when I have been able to have an influence on the ELT provision of a programme it can provide a richer online experience for the learners and benefits their learning by utilising the more interactive tools available through the VLE and other technologies. For example, I was able to advise our DMU Kazakhstan colleagues how to use groups and release condition to provide a more nuanced experience for their separate cohort groups who were studying on the same module.